Hopefully you, dear reader, know what’s going on. If not, turn back to the first episode.

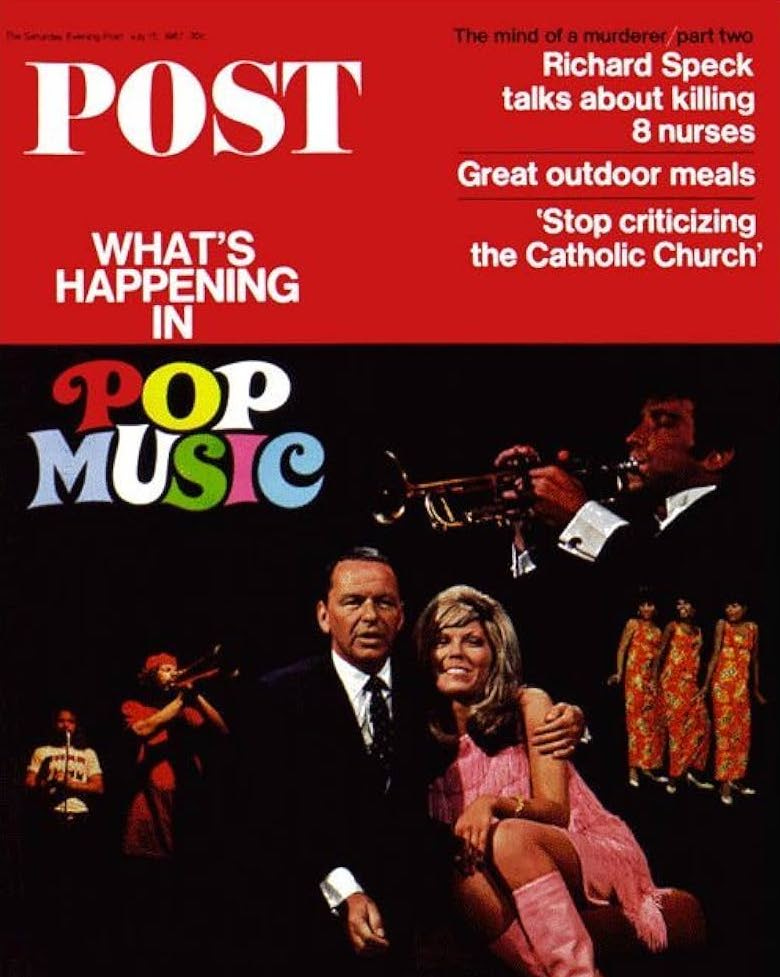

The fourth of the forty-three installments of Points West was published in the July 15, 1967 issue of the Saturday Evening Post. Below is the cover, followed by the piece, “Halfway Home”, by John Gregory Dunne.

If you haven’t the time to read the whole thing this is my favorite part:

“But to be 35 is to be stranded on the highest precipice of the mountain range. Behind stretches the rugged topography of youth; ahead, on a far more even course, the valley of middle age.”

“Halfway Home”

When I was younger, and other people turned 35, I thought it amusing to send a two-word birthday telegram. The wire simply read, "Halfway home." But on the day this spring when I found myself halfway through my allotted threescore ten, the joke suddenly seemed pallid. Perhaps it is because I am beginning to find the names of classmates appearing in the obituary notes of my college alumni magazine. "After a short illness.the notice begins. It is a chilling phrase. There was at least something youthful and abandoned about a drunken-driving accident or skiing into a tree. Now I note on my calendar the date of my annual medical checkup. I examine myself for lumps and bumps and I have heard with sinking heart a doctor tell me that he was sending a piece of tissue "down for a biopsy." When one is 20, he feels immortal. But to be 35 is to be stranded on the highest precipice of the mountain range. Behind stretches the rugged topography of youth; ahead, on a far more even course, the valley of middle age.

And yet I am far happier than I was at 25. Life then seemed full of wild and largely implausible options. Ten years ago I put up $100 to buy a piece of an antimony mine in Thailand. I wasn't sure what antimony was, but I saw myself in riding boots and a wide-brimmed hat in the jungles of Siam. There was a whisper of opium and the freedom of self-exile. The thought, of course, was compensation for the reality I was then living. I was writing advertising copy for a product called Carborundum and I was living at a fashionable address on the upper East Side of New York. I never told anyone, not even the girl I was then supposed to marry, that the fashionable address was a rooming house. It was populated by men who had been beaten by the city. My roommate was a lawyer from South Carolina who had failed the bar exam three times; he was replaced by a drunk who had been out of work for 11 months. I insisted to myself that I was not like them. Noontimes I haunted the seedy one-room employment agencies along Broadway, looking for another job. I felt that if I could only break through to $75 a week, it would be the first step to the cover of Time. By night I concocted résumés, listing jobs I never held. Even now I sometimes wake in the middle of the night remembering the awful day when an employment agent with rheumy eyes and dandruff flaking down on the shoulders of his shiny blue suit told me he had checked one of my references, who reported that he had never heard of me. I survived, as most of us do. The last three years have been, by and large, the happiest of my life. There are a number of reasons, and except for the first, I list them in no special order. I married. I quit my job and moved to Los Angeles, into a vast, old, rented house. I suppose the operative word is "rented." It hints at the kind of vagrant life I prefer. Going into escrow implies a commitment I am not yet willing to make. When one reads other people's books and sits on other people's chairs as a life style, he feels free to pick up at a moment's notice to take the Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok. So far I have not been to Vladivostok, but I know where the courthouse crowd hangs out in Independence, Calif., and where to find the contrabandistas in Nogales, Ariz., and who is the most successful madam in Winnemucca, Nev., and the biggest bookmaker in McCook, Nebr., as well as one or two other things I might never have known had I a patio to brick, a home to stay home in.

I learned I could make a good living without the crutch of a weekly paycheck. I was free to travel, free to turn down what I did not want to do, suddenly so professionally confident that instead of comparing myself to my contemporaries, I compared them to me. There are pitfalls, of course. It is sometimes hard to keep this confidence in balance. More than one bank manager has told me, when I applied for a loan, that I was "technically unemployed." I live for the mail and the checks it is supposed to bring. When they come, and I feel flush, my life dissolves into euphoria, the most chronic symptom of which is procrastination. I make dentist's appointments, I make lists, I plan parties I will never host. A spurious errand--who embedded the axe in Trot-sky's skull?-keeps me in the library for days. I play with my year-old daughter. I had always been indifferent to children and, though I made the usual disclaimers, I did not want any of my own. Now when I watch her climbing the stairs, looking back at each step for a round of applause, I know I was wrong. I was wrong about some other things too. "Cleverness" no longer seems the virtue it once did. I am not so sure any more that the world turns exclusively on sexual passion, nor do I think that getting rich would blight all my dreams. Perhaps everyone knows the same things at 35. But that is all I can tell you, for I am overguarded, disinclined to self-analysis. In making that admission, I know that I will never be a writer of fiction; a storyteller, perhaps, but not what I wanted to be more than anything else. Not long ago, in the hours after midnight when the ice had run out and everyone had drunk too much, I played a game called "Truth in the company of a much-troubled, much-analyzed writer, a movie producer on the make, and one of the first ladies of the silver screen. The game consisted of drawing up two lists of the things you "loved" and "hated" most in the world; the players then tried to guess who made what lists. The first item on the star's "love" list was "making it"; she followed this with "the warmth of a baby's kiss" and "a solitary walk on a rainswept beach." I wrote down Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene. You see what I mean when I say that I am guarded. Politically I feel, at 35, like a ship without a port. Stokely Carmichael recently referred to me, on The David Susskind Show, of all places, as "a white middle-class liberal." I am unable to do much about being white or middle class, however pejorative those adjectives were meant to be. It is the "liberal"* I object to. That is a bag I opted out of a long time ago. I belong generically to the Left, and suppose I always will, but the Left I espoused has lost its sense of skepticism about itself, and in so doing has become intolerant. Liberals will defend to the death your right to agree with them; any other point of view is irrelevant, if not downright obdurate or ignorant, and therefore unworthy of serious consideration. Their cause, and mine too, has become an orthodoxy confounded by its own conundrums. "How did it come about," Malcolm Muggeridge once asked, that the pursuit of happiness led to larger and more crowded psychiatric wards, of knowledge to ever greater credulity and vacuity, of security to an ever-intensifying sense of helplessness and loss of identity, of affluence to ever-mounting indebtedness, of "health to the consumption of more pills and potions?" I ask and I cannot answer. Perhaps answers are the luxury of the very young and hopeful. At 35, I find myself less and less inclined to look for answers, let alone to offer them. It is hard enough to frame the questions, halfway home. Or let us put it this way: halfway to Vladivostok.

John Gregory Dunne