I “imagined that if I studied them closely enough and practiced hard enough I might one day arrange one hundred and twenty-six such words myself.” Joan Didion wrote this about Ernest Hemingway’s opening paragraph to A Farewell to Arms (appearing in the 1998 New Yorker article “Last Words”).

This provided some foreground to something Didion said 20 years prior. When asked “Did any writer influence you more than others?” Didion told the Paris Review in 1978 that “I always say Hemingway, because he taught me how sentences worked. When I was fifteen or sixteen I would type out his stories to learn how the sentences worked.”

Now, I, Audrey Kalman, humbly embark on a parallel voyage of transcription. I am going to be transcribing each installment of Points West, the Saturday Evening Post column written by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, then broadcasting them as Media Roundup Specials.

There is not a ton to be found about Points West on the world wide web. The following paragraph, written by (LWHS alumnus and) New Yorker writer Nathan Heller lends some insight:

“In the spring of 1967, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, freelance writers married to each other and living in Los Angeles, were engaged to write a regular column for the Saturday Evening Post. This was a good gig. The space they had to fill was neither long nor short—about twelve hundred words, a gallop larger than the Comment that opens this magazine. The Post paid them well, and Didion and Dunne each had to file one piece a month. The column, called “Points West,” entailed their visiting a place of West Coast interest, interviewing a few people or no people, and composing a dispatch. Didion wrote one column about touring Alcatraz, another on the general secretary of a small Marxist-Leninist group. The Post was struggling to stay afloat (it went under two years later), and that chaos let the new columnists shimmy unorthodox ideas past their desperate editors. Didion’s first effort was a dispatch from her parents’ house. A few weeks later, her “Points West” was about wandering Newport, Rhode Island. (“Newport is curiously Western,” she announced in the piece, sounding awfully like a writer trying to get away with something.)”

In the next paragraph, Heller writes: “(Their Post rates allowed them to rent a tumbledown Hollywood mansion, buy a banana-colored Corvette Stingray, raise a child, and dine well.)”

(quoted from “What We Get Wrong About Joan Didion” from 2021)

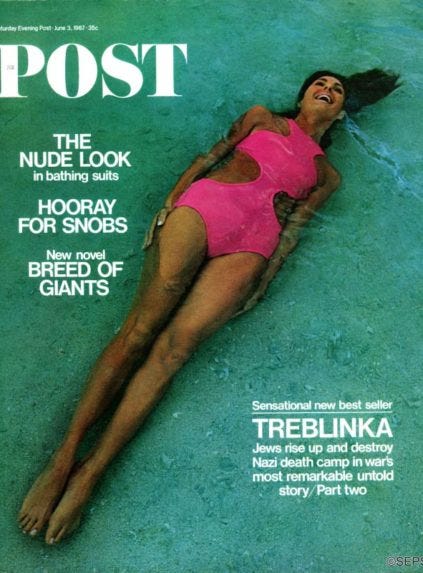

That rounds out the color commentary (of any interest) that I was able to find on Points West. The first of the forty-three installments was published in the June 3, 1967 issue of the Post. Below is the cover, followed by a foreward that appeared in the issue, then the inaugural piece, “Going Home”.

“About this issue”:

This issue inaugurates a new feature, Points West—a column of commentary from the Los Angeles vantage point of John Gregory Dunne and his wife, Joan Didion. Dunne, 35, a former Time editor, has written for the Post on such diverse subjects as baseball, race riots, and the struggles of a labor organizer. Joan, a novelist (Run, River), has reported from New York to Hawaii on murder, lost love, and Christmas puddings.

“Going Home”

I am home for my daughter's first birthday.By "home" I do not mean the house in Los Angeles where my husband and I and the baby live, but the place where my family is, Sacramento. It is a vital although troublesome distinction. My husband likes my family but is uneasy in Sacramento, because once there I fall into my family's ways, which are difficult, oblique, deliberately inarticulate, not my husband's ways. We live in Sacramento in dusty houses ("D-U-S-T," he once wrote with his finger on surfaces all over the house, but no one noticed it filled with mementos quite without value to him (What could the Canton dessert plates mean to him? How could he have known about the assay scales, why should he care if he did?), and we appear to talk exclusively about people we know who have been committed to mental hospitals, about people we know who have been booked on drunk-driving charges, and about property, particularly about property, land, price per acre and zoning and assessments and freeway access. My brother does not understand my husband’s inability to perceive the advantage in the rather common real-estate transaction known as “sale-leaseback,” and my husband in turn does not understand why so many of the people he hears about in Sacramento have recently been committed to mental hospitals or booked on drunk-driving charges. Nor does he understand that when we talk about sale-leasebacks and right-of-way condemnations we are talking in code about the things we like best, the yellow fields and the cottonwoods and the rivers rising and falling and the mountain roads closing when the heavy snow comes in. We miss each other’s points, have drunks and regard the fire. Marriage is the classic betrayal.

Or perhaps it is not anymore. Sometimes I think that those of us who are in our 30’s now were born into the last generation to carry the burden of “home,” to find in family life the source of all tension and drama. The question of whether or not you could go home again was a very real part of the sentimental and largely literary baggage with which we left home in the ‘50’s; I suspect that it is irrelevant to the children born of the fragmentation after World War II. A few weeks ago in a San Francisco bar I saw a pretty young girl on drugs take off her clothes and dance for the cash prize in an “amateur-topless” contest. There was no particular sense of moment about this, none of the effect of “romantic degradation” for which my generation strived so assiduously. What sense could that girl possibly make of, say, Long Day’s Journey Into Night? Who is beside the point?

That I am trapped in this particular irrelevancy is never more apparent to me than when I am in Sacramento. Paralyzed by the neurotic lassitude of home, I go aimlessly from room to room. I decide to clean out a drawer, and I spread the contents on the bed. A bathing suit I wore the summer I was 17, a letter of rejection from The Nation, an aerial photograph of the site for a shopping center my father did not build in 1954. Three teacups hand-painted with cabbage roses and signed “E.M.,” my grandmother’s initials. There is no final solution for letters of rejection from The Nation and teacups hand-painted in 1900. I return them to the drawer, and have another cup of coffee with my mother. We get alone ver well, veterans of a guerrilla war we never understood.

Days pass. I see no one. I come to dread my husband’s evening call, for he asks what I have been doing, suggests uneasily that I get out, drive to San Francisco or Berkeley. Instead I drive across the river to a family graveyard. It has been vandalized since my last visit and the monuments are broken, overturned in the dry grass. Because I once saw a rattlesnake in the grass I stay in the car and listen to a country-and-western station. Later I drive with my father to a ranch he has in the foothills. The man who runs his cattle on it asks us to the roundup, a week from Sunday, and although I know that I will be in Los Angeles I say, in the indirect Sacramento way, that I will come. Once home I mention the broken monuments in the graveyard. My mother shrugs.

I go to visit my great-aunts. A few of them think now that I am my cousin, or their daughter who died young. We recall an anecdote about a relative last seen in 1948, and they ask if I still like living in New York City. I have lived in Los Angeles for three years, but I say that I do. The baby is offered a horehound drop, and I am slipped a dollar bill “to buy a treat.” Questions trail off, answers are abandoned, the baby plays with the dust motes in a shaft of afternoon sun.

It is time for the baby’s birthday party: a white cake, strawberry-marshmallow ice cream, a bottle of champagne saved from another party. In the evening, after she has gone to sleep, I kneel beside the crib and touch her face, where it is pressed against the slats, with mine. She is an open and trusting child, unprepared for and unaccustomed to the ambushes of family life, and perhaps it is just as well that I can offer her little of that life. I would like to give her more. I would like to promise her that she will grow up with a sense of her cousins and of rivers and of her great-grandmother’s teacups, would like to give her home for her birthday, but we live differently now and I can promise her nothing like that. I gave her a xylophone and a sundress from Madeira, and promise to tell her a funny story.

Joan Didion